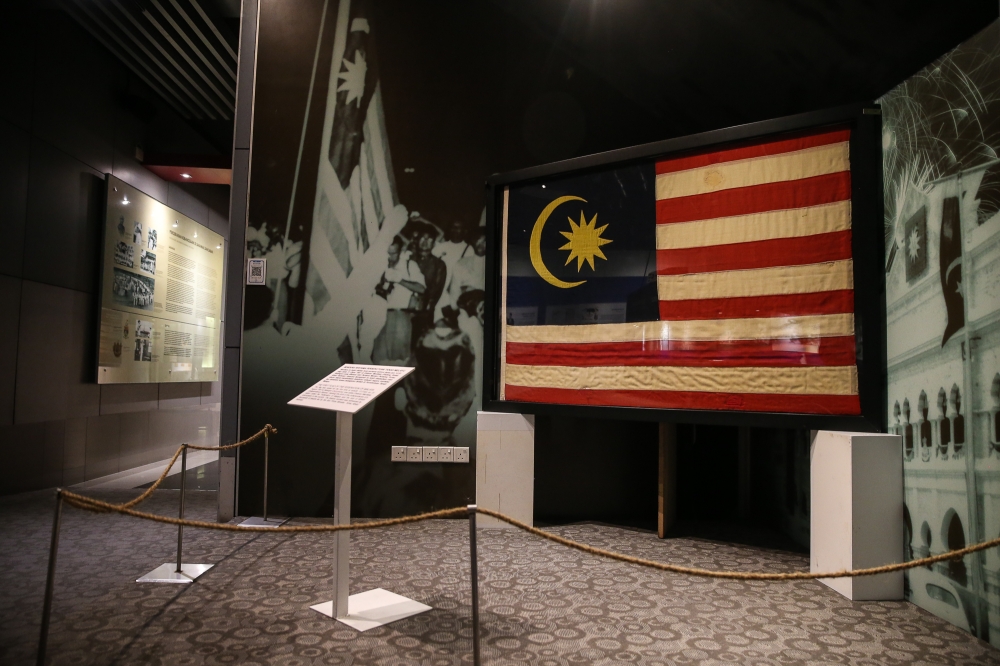

KUALA LUMPUR, June 28 — In one corner of Gallery D at Muzium Negara, visitors will find the original Bendera Persekutuan Tanah Melayu.

The flag was raised at the Selangor Club Padang (now Dataran Merdeka) after the British Union Jack was lowered on August 31, 1957, at midnight.

To Muzium Negara Deputy Director Nor Hanisah Ahmad, it is one of the most important artefacts in the museum’s collection.

“That flag is authentic — it’s not a reproduction. Some people might think it’s a copy, but it’s the real one,” she said.

“It’s proof that when we gained independence, we started as a federation of 11 states. It marks the moment we took back our identity,” she added.

Designed by Mohamed Hamzah, a 29-year-old Public Works Department architect, the flag was selected through a national design competition in 1949 and refined under the guidance of Datuk Onn Jaafar.

To involve the public in the decision, The Malay Mail ran a national poll, with the results published on November 28, 1949. Mohamed Hamzah’s entry emerged as the firm favourite.

The final version — 11 alternating red and white stripes representing the original states, a blue canton symbolising unity, and a yellow crescent and star for Islam — received royal assent from King George VI in May 1950.

Seven years later, it was hoisted in place of the Union Jack as Malaya declared independence.

For Nor Hanisah, the flag is not just a symbol; it is a chapter in a much longer story.

“You can’t just look at one piece. You need to see the whole journey, how we went from prehistoric times all the way to becoming a modern nation,” she said.

Muzium Negara Deputy Director Nor Hanisah Ahmad posing in front of Gallery B of the museum. — Picture by Yusof Mat Isa.

That journey begins in Gallery A, where the museum’s narrative starts with prehistoric Malaya.

Here, visitors will see tools used by early humans, such as stone axes for hunting and food preparation.

“We need to understand how our ancestors lived before technology, before modern systems,” Nor Hanisah explained.

“There were no knives, no kitchens. They used stone tools to survive, to hunt, to skin meat. It shows how humans adapted with what they had.”

The museum then takes visitors through the transition into the Metal Age, when early humans began using underground metal ores to forge stronger tools — a leap forward that laid the foundation for organised communities.

“At first, they just used what was on the surface — rocks, stones. But then they discovered metal in the earth, and that changed everything. Suddenly, they could create better tools than before. That’s where civilisation really starts,” she said.

In Gallery B, the narrative shifts to early Malay kingdoms and regional power structures.

But Gallery C, Nor Hanisah said, holds one of the most crucial artefacts for understanding Malaya’s colonial past: the Pangkor Treaty table.

“I really think people should stop and look at the Pangkor table. That’s where it all began — the British started interfering in the internal affairs of the Malay states,” she said.

Diorama of the Pangkor Treaty signing table, marking the start of British intervention in the Malay states, displayed at Muzium Negara. — Picture by Yusof Mat Isa

Signed in 1874 between Raja Abdullah of Perak and Sir Andrew Clarke, the Pangkor Treaty marked the start of formal British intervention in Malaya.

It recognised Raja Abdullah as the legitimate Sultan of Perak in exchange for him accepting a British Resident, who would advise on all matters except Islam and Malay customs.

That Resident was J.W.W. Birch, the first in a long line of colonial administrators who would influence state affairs.

The model was soon replicated in Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, and Pahang, leading to the formation of the Federated Malay States in 1896 — a structure designed primarily to secure British economic interests, especially in tin and rubber.

“It’s a turning point we must remember,” Nor Hanisah said.

A visitor observing ancient artefacts in Gallery A of Muzium Negara, which showcases Malaya’s early history. – Picture by Yusof Mat Isa

She emphasised that the museum’s four galleries, arranged chronologically, are designed to help Malaysians make sense of their national story.

“Each gallery has its own strength. We want people to walk through and understand how everything connects — from stone tools to the flag, from ancient survival to national independence,” she said.

For Nor Hanisah, every artefact matters, not because of its rarity or visual appeal, but because of what it reveals.

“Every single collection here carries meaning. Every one of them tells a story — sometimes, a thousand and one stories behind a single object,” she said.

In a time when historical literacy is often taken for granted, Nor Hanisah hopes the museum’s artefacts will continue to speak, quietly but powerfully, to every Malaysian who walks through its doors.