DECEMBER 12 — Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul’s sudden move to dissolve parliament and call a snap general election has caught South-east Asia by surprise.

It is a decision that appears bold on the surface — even admirable — but it is also deeply rooted in the slippery realities of Thai politics, where coalitions shift rapidly, parliamentary threats multiply overnight, and governments can collapse long before they complete their mandate.

The timing amplifies the shock. Thailand is under immense internal and external pressure.

The Kuala Lumpur Peace Accord, signed with fanfare and hope, collapsed on December 8, 2026, barely two months after its signing. The Thai-Cambodian conflict has since escalated into wider confrontations, including airstrikes triggered by casualties along the border.

The region has been reminded once again how quickly South-east Asia’s most delicate frontiers can unravel.

Domestically, Thailand is still recovering from catastrophic floods that inundated Hat Yai and much of southern Thailand after late-November rains in 2025. Entire neighbourhoods were submerged, livelihoods swept away, and major roads rendered impassable.

The Thai military — long accustomed to projecting an image of strength and efficiency — struggled to deliver aid swiftly. Disaster-management agencies were overwhelmed. Public frustration spread quickly across the provinces.

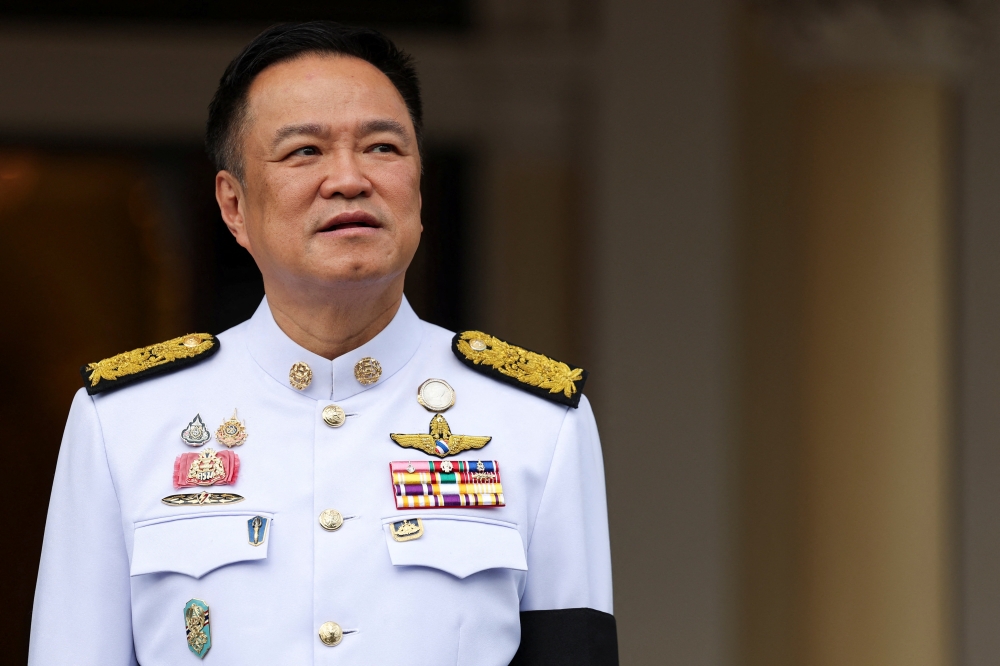

Thailand’s Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul looks on ahead of making offerings to monks, on the day he speaks to members of the media to announce the dissolution of parliament at the Government House in Bangkok, Thailand, December 12, 2025. — Reuters pic

Amid this turbulence, most expected Anutin to consolidate power. Thailand has a long history of turning crises into political shields.

A war cabinet, justified by the conflict with Cambodia, would have given the prime minister wide latitude to delay elections, mute criticism and rally the population under a banner of national unity. The political logic was straightforward and, in many ways, familiar.

Yet Anutin did the unexpected: he dissolved parliament.

It is a gutsy decision, but it is also inseparable from the unstable mathematics of a minority-led coalition.

His government was facing the real prospect of a No-Confidence Motion that he and his party were almost certain to lose. The numbers were shifting. Coalition partners were restless.

The opposition smelled blood. Within Bangkok’s political circles, it was widely understood that Anutin’s days were numbered if parliament were allowed to proceed with the debate.

In Thai politics, losing a No-Confidence Motion is the harshest form of political defeat. It signals weakness, fractures coalitions, and invites elite intervention.

Leaders who fall in parliament rarely recover quickly. For Anutin, the writing was on the wall. Calling an election before parliament could remove him allowed him to reclaim agency at the moment he stood to lose it the most.

This is where Thai politics shows its slippery side: courage and self-preservation are never fully separable. Anutin’s move was brave, but it was also strategic.

By jumping first, he denied his opponents the satisfaction of pushing him out. He reset the political playing field and forced all parties — Pheu Thai, Move Forward’s successors, conservative factions, and military-aligned blocs — into a campaign they had not expected so soon.

The regional context adds further complexity. The Thai–Cambodian conflict is evolving in unpredictable ways. Airstrikes, retaliatory shelling, and cross-border movements have drawn concern from Asean, the United States, China, and the European Union. What began as localised disputes has expanded into broader confrontations linked to crackdowns on scam centres in Cambodia and Myanmar, which themselves are tied to transnational criminal networks operating in the shadows of regional instability.

At the same time, the upcoming South-east Asian Games from December 9-20, 2025, carry their own political undertones. National pride often surges during major sporting events. Strong performances can soften public anger and create a temporary sense of unity. Whether intentional or not, the electoral season overlapping with the Games could shift public sentiment in ways that favour Anutin or at least dilute the intensity of criticism.

But Thailand cannot escape the structural pressures it faces. The floods devastated communities already struggling with rising living costs. The war with Cambodia is draining resources that should have gone into rebuilding. Tourism, a cornerstone of the Thai economy, is jittery. Investors are watching closely. The Thai public, fatigued by repeated cycles of political conflict and intermittent military influence, is demanding clarity and accountability.

By dissolving parliament, Anutin hopes to convert crisis into recalibration. He is gambling that Thai voters will recognise his decision as an act of democratic respect — a willingness to return power to the people rather than cling to it as governments in similar circumstances might. It is a bold narrative to construct, especially when the alternative narrative — that he acted to avoid certain parliamentary defeat — is equally persuasive.

For Asean, Anutin’s decision matters because Thailand remains a central pillar of mainland Southeast Asia, both in economic and strategic terms. Instability in Thailand ripples outward. Cambodia is already locked in a conflict with its neighbour. Myanmar remains engulfed in protracted violence. Laos is struggling with debt and inflation. Malaysia and Singapore are watching the Thai-Cambodian tensions closely, mindful of the broader implications for regional security.

An election in Thailand, especially one called under these conditions, introduces both uncertainty and opportunity. It could bring fresh leadership with a more coherent plan for stabilising the Thai-Cambodian border. It may also produce yet another coalition as fragmented as the current one, prolonging the instability.

But what is undeniable is that Anutin has changed the political script. He refused to use war as a pretext to extend his rule. He jumped before a parliamentary defeat could topple him. He took a risk that very few Southeast Asian leaders take when facing simultaneous war, disaster and political vulnerability.

This is why he appears gutsy.

And this is why Thai politics remains slippery.

In dissolving parliament, Anutin has forced Thailand into an electoral moment it did not expect but perhaps desperately needs. Whether this restores stability or deepens uncertainty will depend not only on the campaigns ahead but on whether Thailand’s institutions — military, political and civilian — can finally accept that long-term stability requires more than tactical manoeuvres.

Thailand now stands at a crossroads shaped by crisis, conflict, and the courage — or calculation — of one leader. The region will be watching closely.

* Phar Kim Beng is a professor of Asean Studies and director at the Institute of International and Asean Studies, International Islamic University of Malaysia.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.