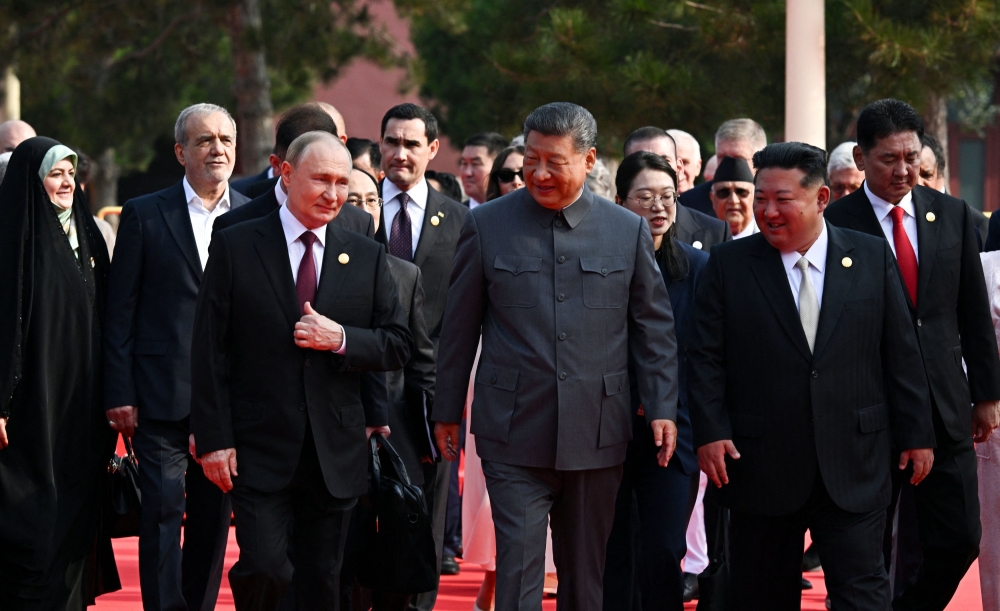

SEPTEMBER 6 — When President Xi Jinping, President Vladimir Putin, and Chairman Kim Jong-un appeared together at Beijing’s Victory Day parade on September 3, 2025, the global optics were electrifying. Some observers dismissed the spectacle as little more than grandstanding, a showcase of military hardware designed for domestic audiences; even foreign buyers.

Yet to reduce it to mere theatrics and sales pitch would be dangerously naïve. The alignment of these three leaders, standing shoulder-to-shoulder, no matter how complicated can be there actual inter personal relationship, reveals a gathering storm that Asean, and indeed the wider world, cannot ignore now or in future. Why?

This year’s parade marked not only the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II but also a decisive step toward consolidating a strategic triangle that could shape the twenty-first century.

Each of the three leaders projected different but complementary messages. Xi sought to confirm China’s centrality, positioning Beijing as the indispensable hub of global power on the right side of history.

Putin demonstrated Russia’s refusal to bow under sanctions and Western pressure, instead embedding Moscow more deeply into Asia’s orbit. Chairman Kim, for his part, shed the pariah status that has dogged him for decades, presenting himself as a global player in the company of two great powers. Even bringing his young daughter to Beijing.

Most striking, however, is that this triumvirate is not bound together merely by ceremonial symbolism. China, Russia, and North Korea are all nuclear weapons states.

The implicit reminder of their combined deterrent power is sobering. While China and Russia have long occupied recognized seats at the nuclear table, North Korea’s arsenal has often been dismissed as crude or limited. Yet the fact remains: Pyongyang possesses warheads capable of destabilizing East Asia, and its inclusion in this coalition magnifies the potential risks exponentially. In his trip to South Korea last November 2024, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim was quick to warn of the nuclear threat posed by North Korea to other countries in the whole of South-east Asia; not just North-east Asia.

Moreover, North Korea is no longer a passive participant in global crises. Reports confirm that Pyongyang has been directly supplying Russia with military and strategic assistance in Ukraine, from artillery shells to tactical cooperation. Since 1945, an Asian power is directly involved in a European war, making it a Eurasian one even.

This shift matters. It means that North Korea is no longer just a silent nuclear actor — it has become a stakeholder in one of the world’s largest and bloodiest conflicts since 1945.

Russia’s reliance on North Korean support underscores its desperation, but also highlights the depth of their strategic partnership. That this alliance was displayed so openly in Beijing adds to the sense that the world is moving into a new, more dangerous phase of multipolar confrontation.

President Xi Jinping, President Vladimir Putin, and Chairman Kim Jong-un at Beijing’s Victory Day parade. — Reuters pic

The United States was conspicuously absent. What makes this omission striking is not merely the lack of an American presence but the deliberate nature of the exclusion.

President Donald Trump, now in his second term, has met both Putin and Kim before. He even famously crossed into North Korean territory during his first presidency. Yet the guest list in Beijing left no room for Washington. This was a purposeful act, designed to signal that China is willing — and able — to convene alternative poles of power without reference to the United States.

For Asean, the implications are profound. How? First and foremost, geopolitical realignment is accelerating even if Beijing, Moscow and Pyongyang will never always see eye-to-eye.

The fact of the matter is China-Russia-North Korea nexus now has a public face. If perception is a reality, then the Xi-Putin-Kim photo ops can be the baseline reality indeed.

If this is the case, then it is a coalition that already combines nuclear armament, economic resilience, and shared grievance against Western dominance.

In South-east Asia, Asean nations tend to rely on balancing strategies to navigate a delicate equilibrium between Washington and Beijing. The growing cohesion of China-Russia and North Korea, no matter how imperfect this triple entente can be — since each has their own angst against each other too — complicates Asean’s already delicate diplomacy.

Second, the risks of polarisation are intensifying. Asean has prided itself on neutrality and centrality, but neutrality becomes harder to sustain when one bloc is willing to display such open defiance of the United States. Washington will inevitably expect Asean members to demonstrate loyalty, especially as trade, technology, and security commitments grow. Beijing, meanwhile, will lean on Asean to show understanding of its “multipolar vision.” The margin for manoeuvre shrinks as both sides harden their positions.

Third, Asean faces an opportunity — and a responsibility — to assert strategic autonomy.

The region has long resisted being dragged into binary choices. The parade is a reminder that Asean’s collective voice must grow sharper. Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta, and Bangkok cannot afford to interpret such events as mere shows of force; let alone sophisticated military gadgetry.

Instead, the Group Chair of Asean must use its institutional platforms — from its Asean Summit to East Asian Summit — to insist on dialogue, de-escalation, and multipolar stability.

Asean cannot afford complacency. The parade in Beijing was not a fleeting spectacle; it was a statement of intent. A coalition of three nuclear-armed states, one of which is already directly engaged in a major European war, is a serious development with global repercussions. The potential for this alignment to extend its influence into maritime disputes in the East China Sea, or to alter the balance of negotiations in the Korean Peninsula, is immense.

For Asean, whose prosperity depends on open sea lanes, stable trade, and predictable diplomacy, the stakes could not be higher.

Some might argue that such alignments are fragile, held together by little more than shared animosity toward the United States. That is partially true. Russia needs China’s markets, China values North Korea as a buffer, and Kim requires both patrons for survival. Yet fragility should not be mistaken for irrelevance. Even an opportunistic coalition can exert enormous pressure, particularly when nuclear arsenals and active wars are involved.

The task for Asean is not to pick sides but to reinforce its role as a stabiliser.

This means investing in collective defence dialogues, strengthening Track II diplomacy, and preparing for scenarios where external powers test the region’s unity. The Asean and East Asia Summits on October 25 and 26 respectively, provide an opportunity to chart a vision of multipolar coexistence. The Beijing parade is a reminder that such vision is urgently needed.

In conclusion, the Victory Day gathering was not mere showboating. It was a demonstration of nuclear solidarity, geopolitical defiance, and strategic intent. China, Russia, and North Korea have chosen to reveal their partnership in the most public way possible. For Asean, to ignore this would be perilous. The region must read the signs, sharpen its diplomacy, and ensure that South-east Asia remains a space for peace, not a pawn in a great-power game.

*Phar Kim Beng, PhD, is the Professor of Asean Studies and Director of the Institute of International and Asean Studies (IINTAS) at the International Islamic University of Malaysia.

**This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.