FEBRUARY, 19 — President Donald Trump, now serving his second term in the White House, has once again demonstrated his instinct for bold diplomatic performance.

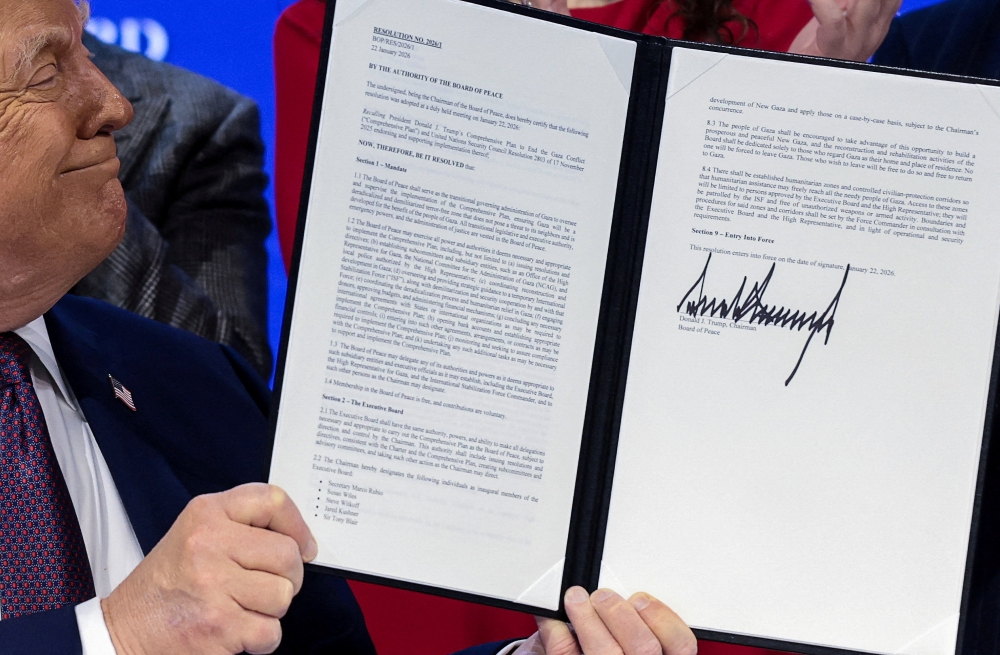

The launch and formal meeting of his “Board of Peace” in Washington is emblematic of his style: large in ambition, disruptive in design, and unapologetically American in leadership.

But is this Board of Peace truly a grand strategic chessboard capable of reordering global diplomacy? Or is it merely a parallel forum that risks duplicating institutions that already exist?

According to reporting by Al Jazeera, the Board of Peace is envisioned by President Trump as a potentially transformative international body. He chairs it personally.

It was initially designed to focus on Gaza’s post-war stabilization and reconstruction, but its mandate appears fluid and expandable.

Trump has even suggested that it could become one of the most consequential international platforms in history.

The inaugural meeting gathers more than twenty countries.

Among them are key regional actors such as Indonesia, Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

Israel is also participating — a significant factor given the Board’s immediate focus on Gaza.

Yet conspicuously absent are several major Western powers. France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the European Union have not fully embraced the initiative.

The Vatican has declined participation outright, signaling that peace diplomacy should remain within the framework of the United Nations.

This divergence immediately frames the Board’s central dilemma: ambition without universal legitimacy.

The first agenda item is Gaza. Over five billion US dollars in reconstruction pledges are expected to be unveiled.

Discussions include the establishment of an International Stabilization Force to secure Gaza, support governance, and facilitate humanitarian recovery.

In principle, reconstruction is necessary. Gaza’s infrastructure has been devastated over years of recurring conflict.

Roads, hospitals, schools, water systems and electricity grids require urgent rehabilitation. No serious peace process can ignore the humanitarian dimension.

However, reconstruction is not peace.

A grand strategic chessboard must do more than mobilize funds. It must address root political grievances, power asymmetries, and enduring security dilemmas.

Without resolving questions of sovereignty, security guarantees, and political representation, financial pledges risk becoming band-aids over structural wounds.

The Board’s emphasis on stabilization forces also raises important questions. Who authorizes such a force? Under what legal framework does it operate ?

How does it coordinate with the United Nations ? And crucially, how does it gain consent from affected populations on the ground ?

Peace imposed without legitimacy is rarely sustainable.

From an ASEAN perspective, this initiative is fascinating. Southeast Asia has long practiced quiet, consensus-based diplomacy.

The “ASEAN Way” privileges inclusivity, non-interference, and incremental confidence-building. It is not dramatic.

It is not theatrical. But it has proven resilient.

President Trump’s Board of Peace is almost the opposite in style.

It is centralized, personality-driven, and unapologetically strategic in optics.

It signals that the United States intends to reclaim leadership in shaping conflict resolution mechanisms rather than defer to multilateral institutions perceived as slow or gridlocked.

Yet therein lies both its strength and its vulnerability.

On one hand, decisive leadership can cut through bureaucratic inertia. The United Nations Security Council has often been paralyzed by veto politics.

A smaller coalition under American leadership may move faster, coordinate funds more efficiently, and deploy resources with greater agility.

On the other hand, bypassing established institutions risks fragmenting global governance.

Peace diplomacy is already crowded: the UN, regional organizations, ad hoc coalitions, Track 2 or Track 1.5 processes, and special envoys all operate simultaneously.

Another platform adds complexity unless it complements, rather than competes with, existing frameworks.

If the Board of Peace becomes perceived as an alternative to the United Nations rather than a reinforcement of it, skepticism will deepen.

Moreover, peace is not a branding exercise.

It is painstaking, often frustrating, and rarely glamorous. Gaza is not a test case for political optics; it is a humanitarian and geopolitical tragedy with layers of historical grievance.

Without addressing Israeli security concerns and Palestinian political aspirations in equal measure, reconstruction funds alone cannot prevent relapse into conflict.

A true grand strategic chessboard would integrate diplomacy, security, economics and legitimacy in one coherent framework. It would link ceasefire mechanisms with political negotiations.

It would ensure regional buy-in from Arab states while maintaining dialogue with Israel. It would align with international humanitarian law and work in tandem with UN agencies.

The Board, at present, appears more focused on coordination and pledges than on structural political settlement.

That does not mean it is doomed to fail. On the contrary, it holds potential — but only if recalibrated.

First, it must clarify its legal and institutional relationship with the United Nations. Complementarity is key. Peace is not a zero-sum competition between institutions.

Second, it must broaden participation to include hesitant European actors. Exclusion weakens legitimacy. Inclusion strengthens durability.

Third, it must anchor reconstruction within a clearly articulated political roadmap.

Without a roadmap, stabilization forces risk becoming temporary caretakers in an unresolved conflict.

Fourth, and most importantly, it must demonstrate early, tangible outcomes.

Schools rebuilt. Hospitals functioning. Ceasefires monitored effectively.

Civilians protected. Peace credibility grows through delivery, not declarations.

President Trump’s second term is already marked by assertive foreign policy gestures.

The Board of Peace fits that pattern. It signals that Washington is unwilling to remain passive in shaping post-conflict governance.

But grand strategy requires more than initiative. It requires patience, coalition-building, and humility before complexity.

ASEAN’s experience offers a quiet lesson.

Durable peace frameworks are built through gradual trust accumulation, not dramatic announcements.

Even the Helsinki Process in Europe — which helped reduce Cold War tensions — evolved through sustained dialogue rather than singular summits.

If Trump’s Board of Peace evolves into a platform that genuinely ends real conflicts — not merely coordinates reconstruction — it could become a meaningful instrument of 21st century diplomacy.

If it remains confined to pledges and prestige, it risks being remembered as another experiment in geopolitical theatre.

A chessboard is only as powerful as the moves played upon it.

The world does not need another stage. It needs fewer wars.

And unless the Board of Peace commits itself to ending real conflicts — not merely managing their aftermath — it will remain a promising but unfulfilled strategic construct.

• Phar Kim Beng is a professor of Asean Studies and director of the Institute of International and Asean Studies, International Islamic University of Malaysia.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.