AUG 25 — STPM graduates are the orphans of Malaysia’s education system. Their plight, as recently highlighted by YB Sim Tze Tzin in his commendable call for a Selamatkan STPM Taskforce, merits a considerate and effective response in line with the 13th Malaysia Plan’s social mobility pillar.

The STPM is a two-year pathway to university, available at numerous schools and a few Form 6 colleges across the country, culminating in a challenging externally-administered national exam.

Matriculation colleges offer a one-year programme, teaching a narrower syllabus in a fully residential setting, where the examination is coordinated internally by the Ministry of Education.

In 2023, 41,548 students took the STPM exam, while 25,239 were enrolled in matriculation, making these two pathways the primary means of access into (the subsidised placement in) public universities.

STPM students outnumber matriculation peers, but they are outscored. The disparity in academic results is stark.

YB Sim disclosed from Ministry of Education data he obtained through parliament showing 3 per cent of STPM graduates obtained the maximum CGPA of 4.0, compared to 16 per cent of matriculation college graduates.

These results are significantly driven by self-selection after secondary school for a number of reasons. Given the public perception that matriculation colleges are “guaranteed” a place in public universities, SPM top scorers, including non-Bumiputera students, would flock to apply.

This is despite matriculation colleges implementing a 90 per cent Bumiputera quota.

Conversely, all students who have not been offered a place in a matriculation college but meet the minimal requirement will receive an offer to enrol in Sixth Form in preparation to sit for STPM.

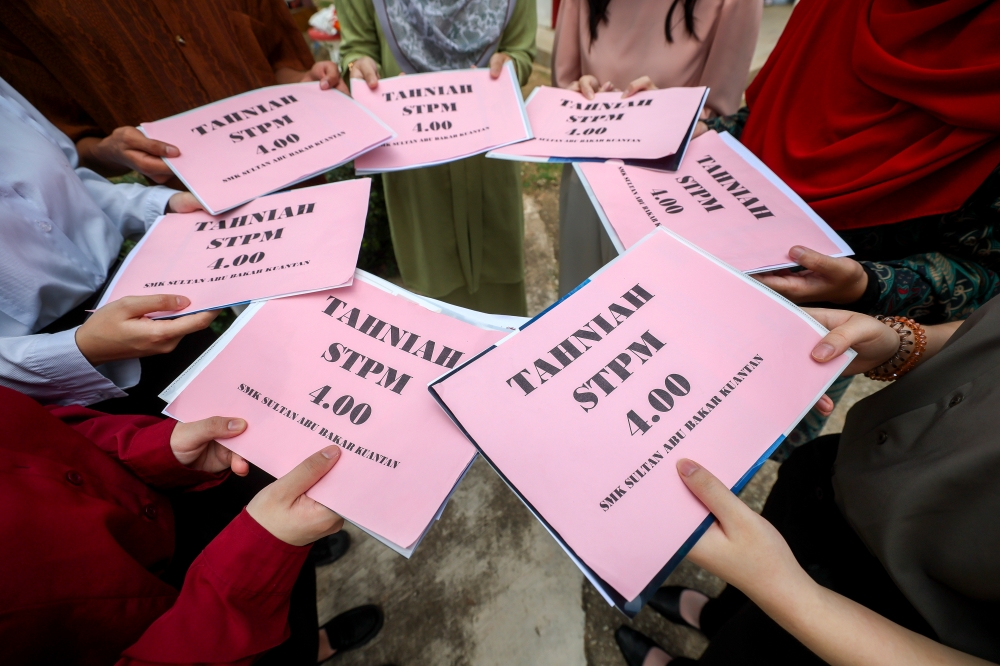

STPM students outnumber matriculation peers, but they are outscored. — Bernama pic

In other words, matriculation college entrants are already higher achieving; the gap between them and STPM students widens further as they progress through pre-university programmes. Importantly, 72 per cent of STPM students are from low-income (B40) households.

The achievement disparity further extends to university admissions. Among the entering cohort of STPM and matriculation graduates to public universities, STPM graduates comprised an abysmal 2.4 per cent (23 per 962) in medicine and 0.9 per cent (2 out of 235) in dentistry.

For the 2018 public university intake, the most recent publicly disclosed data, 24,375 out of 33,197 STPM applicants (73.4 per cent) were admitted to a public university, compared to 20,269 out of 20,907 matriculation graduates (96.9 per cent).

About 9,000 STPM graduates did not make it to a public university that year. Most of them likely could not afford private university fees.

We have tended to focus on top-scoring students and the conventionally popular and prestigious fields, like medicine or law, but the problems with university admissions must be addressed at the systemic level and with a commitment to fairness for students of all backgrounds and diverse achievement levels.

The vast majority are not “straight A” students, and many, especially STPM graduates, might be languishing without a place to go after Sixth Form.

However, the UPU system places matriculation grades on par with STPM grades, which compounds the disadvantages faced by STPM graduates because it is harder to score in STPM’s more expansive and advanced curriculum. .

What can be done for STPM graduates? The system is deeply embedded and seemingly rigid, but we hope that some constructive tweaks are possible, practically and politically.

We suggest three interventions.

First, it is important to recognise that between the two programmes, STPM is more rigorous in breadth and depth.

The most distinctive component of STPM is the compulsory subject of General Studies. Every candidate is required to sit for this subject, which is essential to develop key academic skills in preparation for university, such as analytical skills, presentation of data, and critical thinking.

Equally important, the citizenship component in General Studies is instrumental in developing informed citizens for the nation.

Thus, it may be timely for the university admissions points system to be reconfigured in recognition of the STPM’s strengths.

A more systematic solution would be to decouple STPM and matriculation and not evaluate students from these two programmes using the same template.

A separate evaluation exists in the current system whereby students with other pre-university qualifications, such as the A-levels or International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IBDP), are assessed independently for admission.

In the same vein, the admissions criteria should not equate a distinction in STPM with a distinction in other qualifications, but should rigorously evaluate the pool of STPM applicants.

Second, we should equip STPM students better for their university applications.

They may fare worse in programmes that require interviews, if they lack advisory and coaching help from their school, or are less proficient in English or unaware of language requirements.

Many, especially in smaller schools, might not be provided sufficient information and counsel on university programmes, course selection, and strategies for maximising the chances of their applications.

Providing such service nationwide will be daunting, but instructional videos and engaging content can be disseminated digitally.

Third, the UPU centralised admissions portal officially operates a computerised “meritocratic” system that only considers academic and extra-curricular activity scores, omitting identity traits such as ethnicity, gender, or residential location in the selection criteria.

Yet, the system differentiates students whether they took STPM, matriculation, foundation programmes from public universities, or other pre-university programmes.

One of the recent additions to the UPU portal is publishing the “average merit” for each individual programme for students applying from the STPM, matriculation and foundation programmes route.

This is a progressive move, but we would like to further propose to disclose the admission score over the past two years on the portal, which specifically includes the median, mean, mode, minimum and maximum, as well as the number of students admitted according to the different programmes.

Diverting our attention to look at STPM is an important educational reform, which we believe the 13th Malaysia Plan should pay attention to.

Despite the challenges and poor public perception of STPM, along with superficial interventions to popularise this pre-university pathway, STPM continues to have significant educational and socioeconomic roles to play in the Malaysian education system.

On the one hand, it remains as the most comprehensive and rigorous university preparation programme in preparing students for university.

On the other hand, STPM continues to serve a huge proportion of B40 students.

Neglecting the double disadvantages of STPM students heightens the risk of many missing out on tertiary education. Madani should look out for their interest.

* Dr Lee Hwok Aun is a Senior Fellow with the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. Dr Wan Chang Da is a Professor at the School of Education, Taylor’s University.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.